Visitors to Holy Island often ask us about the best places to see seals on the island. Others look at us nervously and ask: what are those strange moaning sounds we heard last night? Spoiler: these are ‘seal song’, from the grey seal colonies on the sandbanks and nature reserve beaches.

Where can I see grey seals when staying on Holy Island?

Seal spotting on Holy Island itself

Up to 4,000 Grey seals haul out onto the sand flats at Lindisfarne national nature reserve. If you’re lucky and have a keen eye, you might even spot a Harbour seal in the mix.

They seem to move around from year to year, so if you’re staying with us, we may be able to tell you the most recent and best viewing places at the time. That said, there are a few good bets. Colonies congregate on the sand banks between the island and the mainland at mid to low tide. If you take

our recommended walk along the foreshore, you’ll often see large groups of seals on the sandbanks in the distance and hear them singing as well. A good pair of binoculars will serve you well here. There will likely also be some seals in the water between the sandbanks and the island. As the tide rises and forces the seals off the sand, they’ll swim around. Keep your eyes peeled for that grey shape bobbing in the sea.

Another popular seal-spotting place is from the top of the Heugh, and of course you might see them on any of the other beaches as you walk around the island, but that is less predictable.

Seal cruises to the Farne Islands

As you look east and out to sea from Holy Island, you’ll see the Farne Islands. They are 28 islands, some very small and some only visible during low tide. Of these, three are accessible: Staple Island, Inner Farne and Longstone (home to the ‘

Grace Darling’ Lighthouse).

If you’d like a closer encounter with seals (as well as amazing birdlife and

puffins in season), plan to take one of the cruises to or around these islands. The boats leave year round from

Seahouses harbour (about 40 minutes drive from Holy Island). Between April and October, you can land on the islands themselves (May-July only for Staple Island, just in time for peak puffin season).

These trips will typically take you to see the seal colony up close first, and also either take you around the islands, or land you on one of them. If you’re lucky you might even spot a whale or some dolphins. Just search for Farne Island cruises. We’ve used Billy Shiel and Serenity, and both were excellent.

When can I see the seals?

The seals are around all year, however, on Holy Island they are barely visible in winter and start arriving in numbers from around the last week of February/beginning of March and then leave towards wintertime. They are easiest to spot during the spring and summer months. In September, on the off-shore Farne Islands, the first seal pups start arriving: small, fuzzy white balls that look like cotton wool. During this time, the seals gather in their thousands on the shores of the Farnes, with the end of October being the peak time for the pups, and the best time of year to be out looking for them on one of the cruises from Seahouses.

What type of seals do we see?

The primary species seen on Holy Island are

Grey seals, also known as Atlantic seals. They spend 80% of their time underwater, diving for around eight minutes (although the longest recorded dive was 30 minutes) and hunting at depths of up to 30 metres. Sand eels make up about 70% of their diet, along with fish, squid and octopus. Seals spend the other 20% their time on the surface; breathing, lolling around and digesting their food. This is when you’re most likely to see them, either bobbing on the water or hauled out on the shore.

There is also a very small number of Common seals, also known as

Harbour seals, found on Holy island. They are very rare, with an average of one recorded per year, however nine were seen in 2010. The Holy Island colony haul-out among the Grey seals on the exposed sandbars at Fenham Flats.

The primary way of telling which seal you’re looking at is by their face – Harbour seals have a shorter muzzle, with v-shaped nostrils that meet at the bottom while Grey seals have flatter, longer head profiles with parallel nostrils that do not meet. A common method used to tell them apart is that Harbour seals are more ‘dog-faced’ due to the dip between their forehead and nose creating a snout, while Grey seals are more cat-like with a rounded profile. This is also reflected in the Grey seal’s Latin name

Halichoerus grypus, which means ‘hooked-nose sea pig’.

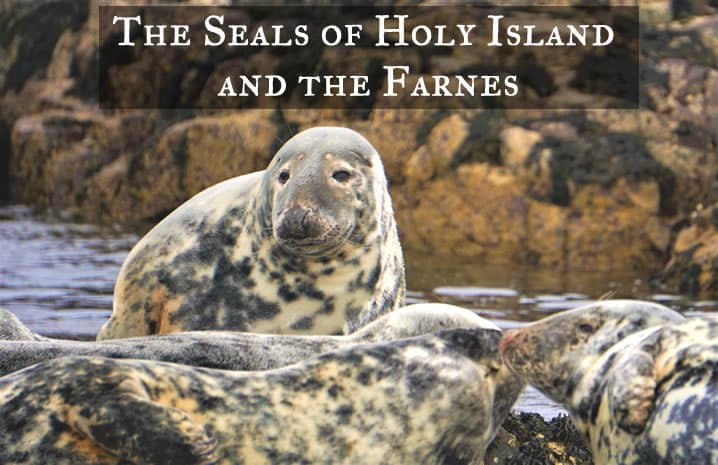

Grey Seals

Although they may look small from afar, Grey seals can weigh up to 300kg and reach 2.6 metres in length. In comparison, Harbour seals are much smaller, weighting up to 170kg and reaching 1.5 metres in length. As with all marine mammals, they are covered in thick layer of blubber that they use to keep their body temperature stable in cold water, and a layer of dense, water-resistant fur. Their fur is often mottled, with darker grey blotches, which is where they get their name from. Pups are born with fuzzy, white fur, which is not water-resistant. At just under a month old, they develop their adult coat so they can enter the sea by themselves.

A party of Grey seals can be a noisy bunch – if the wind is in the right direction, you can hear them calling to each other. They sing a haunting tune, thought to be the siren songs that used to lure sailors to their death!

Seal pups

In the Autumn months, female Grey seals come ashore the islands to pup. Their numbers swell during this time as over 1,500 pups are born across the islands – the highest ever count was 2,295 in 2016.

While the pups are young, the males and females stay on land to protect and feed their offspring with extremely high-fat milk. Since they can’t hunt for food, the parents fast during this time, gaining energy from the blubber they have stored up. The longer a male can stay and defend his territory, the more successful his pups will be – they can fast for over 50 days!

Despite this, the pups still have a difficult childhood. 30% die within a month, and 50% within the first year.

This is often because they are washed out to sea by the rough waves and can’t survive as they are not yet waterproof. After 18 days of drinking their mother’s milk, the pups have quadrupled in weight and are weaned. They then spend another 20 days in the colony before heading to sea to become independent once their water-resistant fur has developed.

Sadly, we don’t know too much about where they go when they leave the colony. The first tracking experiment in the 1950’s found one alive at Jaeren, 20 miles from the south western tip of Norway, having travelled 400 miles in 14 days. This was the first sign that they travel huge distances across the North Sea. A study on German colonies found they move between the Danish, Dutch and UK coastlines, so it is likely the UK colonies also wander around that south-eastern corner of the sea.

The Farne Colony

There’s a reason that Sir David Attenborough called the Farne Islands his “favourite place in the UK to see magnificent nature” – the islands and the surrounding seas are an internationally important wildlife reserve.

Every year, we see an abundance of fantastic British wildlife, including puffins and over 100,000 seabirds.

The Farnes boast one of the third largest colonies of Grey seals on the East Coast of England, providing a home to around 5,000 seals and contributing 2.5% of the annual British pup production.

Since 1952 the Farne seal colony has been monitored and counted, so we have an excellent record of how the populations are doing. For three months every autumn they are visited every four days to monitor breeding success, and new pups are marked with harmless dye to keep an eye on them. This means we know exactly how many are born and how many die every season. Since 2017, the rangers have also been experimenting with drones to follow and track the pups, as this is much less intrusive for the seals and much safer for our rangers.

The seals of the Farnes are the stars of their very own scientific discovery. Dr Burville, a researcher from Newcastle University, was diving off the coast of the Farne Islands when he witnessed a male Grey seal ‘clap’ underwater during breeding season – which he then spent 17 years trying to capture on camera! After the gunshot-like crack, the rival males dispersed quickly, leading Dr Burville to believe that male seals (also known as bulls) use this as a sign of strength to scare off competitors and attract mates.

Conservation

Across the world, the risks to seals are largely caused by humans. There are frequent calls for culls by those who claim seals reduce fish stocks, although there is no scientific evidence for this. Seals, like all marine wildlife, are also regularly caught in fishing gear and marine debris. Because of this, they are protected in Britain under the Conservation of Seals Act of 1970.

The Farnes seal colony is very lucky in that they don’t face many threats, and as such are doing incredibly well, with numbers increasing 57% over the last 5 years. This is due to the lack of predators and a plentiful supply of sand eels. A much-loved addition to the fauna of the islands, the seals are not subjected to high human threat.

The rangers have also noticed a change in the behaviour, with more seals breeding on Brownsman and Staple islands. These islands offer better protection from storms and high seas, preventing wave-wash which can be devastating to pups on low-lying islands which haven’t yet grown waterproof fur.

Nevertheless, it is as important as ever that we look after these animals and retain the beauty of these natural areas. Keeping the waters clean from debris and pollution is beneficial for all the animals that share this environment. If you’d like to help, why not participate in a beach clean and safely dispose of anything that might harm the wildlife.

They may look friendly, but seals are still wild animals that should not be disturbed, particularly during breeding and pupping season. If they feel threatened by your presence, they can become defensive, so please do not approach them, especially with dogs. A cautionary tale is that of the man rushed to hospital in Devon, after he

attempted to pat a seal on the head and was bitten.

If you are unsure if a pup is safe, or if an animal appears injured, please ring the British Divers Marine Life Rescue hotline on 01825 765546 or 07787 433412.

We hope you enjoy your visit to Holy Island and have the opportunity to experience these fantastic animals. If you’re lucky, you may hear the siren’s calls or even see a common seal lolling around Lindisfarne!

Picture credit: Sarah Kilian

Visitors to Holy Island often ask us about the best places to see seals on the island. Others look at us nervously and ask: what are those strange moaning sounds we heard last night? Spoiler: these are ‘seal song’, from the grey seal colonies on the sandbanks and nature reserve beaches.

Visitors to Holy Island often ask us about the best places to see seals on the island. Others look at us nervously and ask: what are those strange moaning sounds we heard last night? Spoiler: these are ‘seal song’, from the grey seal colonies on the sandbanks and nature reserve beaches.