Much of what we know of St. Cuthbert of Lindisfarne appears to be legendary, but every legend must start with a grain of truth. If the stories are any indicator, he must have been a devout man who inspired those around him deeply, despite (and possibly also because) of his love of solitude.

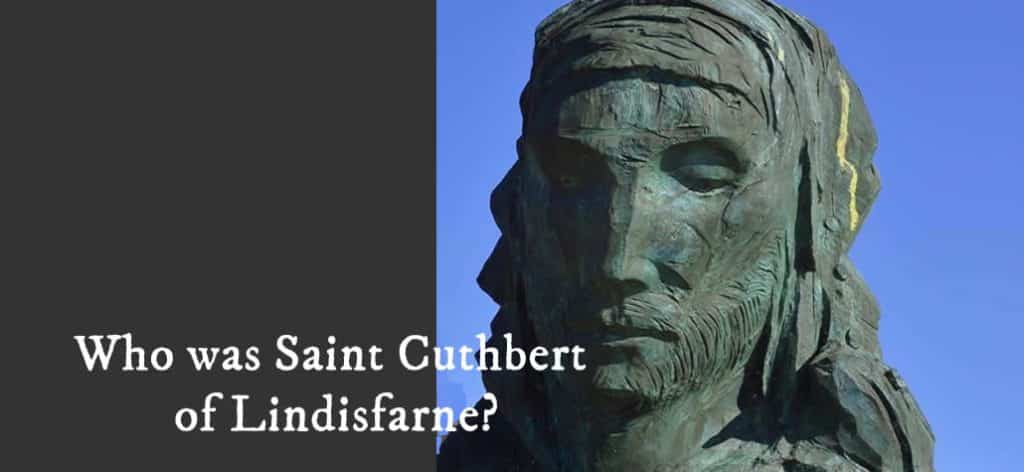

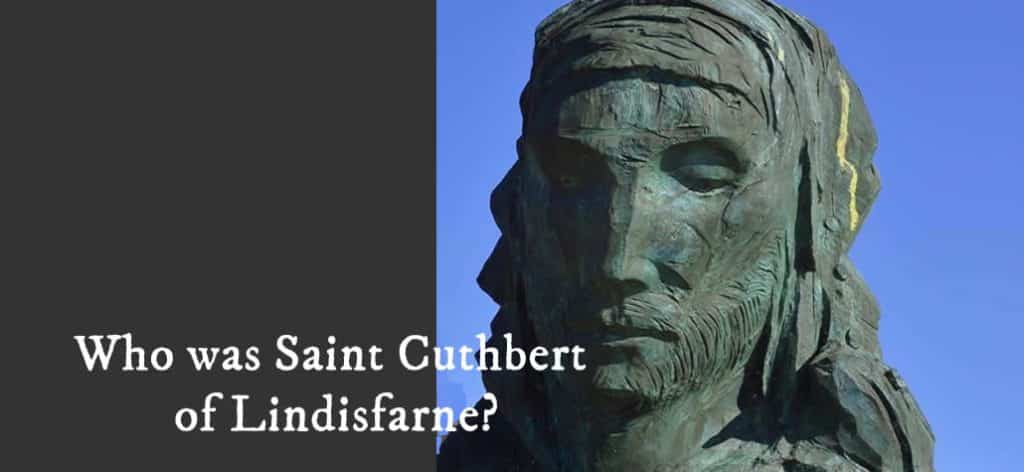

Today, a modern statue of St. Cuthbert stands as a green-grey sentinel of the local priory ruins. His lips are pursed beneath his aquiline nose, his hands folded in contemplation, and his unseeing eyes watch over the Holy Island of Lindisfarne, which he once called home. It isn’t difficult to imagine why Cuthbert’s predecessors, Saint Aidan and his fellow monks, were apt to set up a monastery here. Beyond the practicalities of a fresh water source and green pasture, the isolation of the tides that make Lindisfarne an island twice a day and the sound of breaking waves, and spectacular sunsets all speak to the divinity of the Creator. And standing where Cuthbert stood, it isn’t so difficult to imagine him either – no longer just a figment of stone, but a living, breathing being separated from us only by time.

Shepherd, Soldier, Prior, Saint

Saint Cuthbert, the shepherd

Cuthbert, like many saints, is a man of legend, and the details of his birth are no exception. While historical record, or lack thereof, accounts for the discrepancy in dates (634 or 635), it is most likely legend which gives us the story of a royal heritage (Cuthbert is often rumoured to be the son of an Irish king).

Just like the biblical King David, Cuthbert helped keep sheep when he was a boy. This task no doubt suited young Cuthbert well, for he was a compassionate soul, showing kindness to humans and animals alike. A foreshadowing of things to come, whenever Cuthbert would tear his gaze away from his sheep, the Melrose monastery was there on the horizon. Like King David, Cuthbert was set apart to accomplish great things. The sign came, not through an anointing of oil, but supposedly, through a dazzling vision in the night.

The vision took place in August of 651. The significance of the date may be lost on us now, but it was a bustling time for the Scottish Borders and Northern England – pagan hostilities, the storming of a castle, the murder of a king, and the death of a beloved missionary monk. The monk’s name was Aidan. He was also the founder of the monastery in Lindisfarne and credited with restoring Christianity to Northumbria. His death was a reflection of his life: he passed away in the night leaning on the wall of the local church. It was news of this monk, even more than rumours of war, that would shake Cuthbert to his core.

Back in Melrose, Cuthbert was keeping watch over his flock by night – the same night of Aidan’s death. Then suddenly, as recorded by the venerable Bede, a long stream of light illuminated the night, interrupting Cuthbert’s diligent prayers and startling the sheep. Cuthbert watched intently as a heavenly host appeared, descending to the earth to gather up another spirit into their midst. This spirit – whoever it was – was remarkably bright, and the angels escorted them to their heavenly home, leaving behind only the light of the winking stars.

Needless to say, Cuthbert was flabbergasted. However, the matter became clear to him the next morning when he learned of Aidan’s death; he believed he had watched Aidan’s soul being taken to heaven. It was at that moment he knew the monastery was no longer to be a shadow on the horizon but his home.

Saint Cuthbert, the soldier

Unfortunately, the rumours of war became reality, sweeping Cuthbert away from his calling for a time as he served in the military. His precise actions in the Northumbrian army are unknown, but it is believed he took part in its battles against Mercia, Northumbria’s pagan enemy and bitter rival. Surviving even a single battle of the era was a feat in and of itself. The warfare was constant and fraught with bloodshed, frantic with swinging swords and frightening in its utter brutality. For the shepherd boy who preferred offering prayers up to God, it must have been a grim prospect to offer up pagan souls upon a sword’s edge instead. Perhaps even more disturbing to Cuthbert would have been the numerous reports of slaughtered monks, the people he so desperately wished to join. It is little wonder the Bede said of him that “he preferred the monastery to the world.”

Saint Cuthbert the monk

After the war, Cuthbert was finally able to join the monastic life he felt called to, and he journeyed several days to reach Melrose. It was winter, and one can imagine flakes of snow sticking to his cloak, snuggly wrapped about his shoulders. He was riding down a long stretch of road with no inhabitants; he and his horse were the only living things wandering the cold land that day. He had no more food with him, and there was no house where he could beg for shelter. Cuthbert looked to the distance and saw a dilapidated shepherd’s hut.

As Cuthbert sheltered there for the night, one must wonder if he thought back to his own shepherding days, which must have seemed a lifetime ago, an impossible peace, after the experience of war. As Cuthbert settled in for some much-needed rest, he said his prayers, then took a handful of straw from the thatched roof to feed his horse, his own belly empty and grumbling. Legend states that out of the straw a cloth bundle fell to his feet containing freshly baked bread and meat. Cuthbert gave thanks to the Lord for His miraculous provision, then he is said to have split the loaf of bread with his horse, rather than feeding it stale straw.

Bellies full and hearts warmed, Cuthbert and his horse braved the wintery weather once more and reached their destination: Melrose monastery. As Cuthbert rode up to the monastery, it is said a monk at the door cried, “Behold! A servant of the Lord!” He spoke truly, for Cuthbert went above and beyond the duties that were laid out before him – in prayer, study, and labour. You can almost hear Bede chuckle when he says of Cuthbert, “he fairly outdid them all!” For Cuthbert there was no contest though; he was not trying to outdo anyone, he was just being himself. He has been described as affable, pleasant, and incredibly meek when prompted into divulging his miraculous experiences.

Saint Cuthbert, the prior

In 662 Cuthbert was made prior at Melrose after a bout of plague had killed the previous prior. It must have been a bittersweet experience for Cuthbert; he would have been hurting with grief from the death of a friend, yet taking a flock under his wing and getting to call them his very own. During this time of hardship, Cuthbert, too, became sick. Just like surviving a battle, surviving plague could very well be counted a miracle, as 80 percent who contracted it would die within eight days. As soon as Cuthbert recovered, he went out into the countryside, helping other plague victims. The elevation in rank from monk to prior had increased not his pride but his servant’s spirit.

Cuthbert continuously followed Christ’s command to go and preach to the world. For years he travelled from village to village, serving the people and preaching God’s Word; he even travelled into the destitute, mountain villages which could easily have been neglected. Not only did Cuthbert travel to such places, but he would live among the people for weeks, even a month at a time, demonstrating the love of Christ through his actions, just as much as he did through his words. That Cuthbert did not discriminate between rich or poor when giving aid or guidance further endeared him to those who knew him.

While Cuthbert was at Melrose, however, there was strife in the larger church community. For as long as anyone could remember, Northumbria had followed the practices of the Celtic Church, but then the king married a woman of the Roman Church. The two churches appeared to be compatible, but ended up having some key differences. The Celtic Church favoured autonomy, had a different dating of Easter, and different liturgies; these things were seen as especially problematic by the Roman Church. A council was formed to sort the matter out, and ultimately the Roman Church won out. Cuthbert, previously a Celtic, must have agreed with the change, because he was asked to introduce the new practices at Lindisfarne. He was seen as a good fit for the task because of his strong leadership, lovingly showing the way by word and example. Cuthbert accepted the task, and became the prior at Lindisfarne monastery in 670.

Interestingly, the soul Cuthbert had seen ascend into heaven was intertwined with this next step in his journey as well, because Aidan had been the first bishop of Lindisfarne, perhaps starting his tenure there around the very time Cuthbert was born. This fact could not have been lost on Cuthbert, and might have eased him in his decision to leave his beloved Melrose. Perhaps he felt it was a renewal of that dazzling sign he had received years previously when he was a mere shepherd boy.

At Lindisfarne, Cuthbert was pitted against his most difficult challenge yet. He sought to teach the monks there the Roman customs, but was taunted in return. The ancient customs were not to given up that easily. However, Cuthbert was a patient man, and according to Bede, never lost his temper with his querulous monks. Through perseverance, he managed to convert them to the newly popular doctrines and practices.

Like at Melrose, Cuthbert did not confine himself to the walls of Lindisfarne monastery, but went on evangelizing, continuing his sacred mission work. It was reported that Cuthbert also performed miracles like the Apostles of old, including healings, exorcisms, and averting disasters through prayer. He became known as the “Wonder Worker of Britain.” Cuthbert kept himself so busy he rarely slept, rest only coming in the form of irregular naps. Even this he loathed to do, and he encouraged his monks to wake him so he could then “do or think of something useful!”

Saint Cuthbert, the hermit

However, six years of nonstop work took their toll on Cuthbert (as they would on any man), and he began to desire a life of solitude and peaceful contemplation. Perhaps he found himself longing for those halcyon days where he prayed surrounded not by walls but by nature, with silent sheep rather than student-monks for company. He accomplished this dream by moving to Inner Farne, a remote and deserted island not too far from Lindisfarne. Although he planned on a life of solitude, the hospitable Cuthbert could not help but build both a home for himself, as well as a second, larger home for any guests that may venture out to his island. (And venture they did). The stones Cuthbert used for his structures were too large for any one man to lift, so it has been recorded as another miracle – he must have been helped by angels in the construction.

Though some traversed the sea to commune with Cuthbert, and were never turned away by him, the waves kept many at bay. Thus, his main company, once again, was of the animal variety but also of miraculous nature. Bede records the repentance of a crow who stole straw from the thatched roof of Cuthbert’s guesthouse. Once Cuthbert had rebuked the black bird in the name of the Lord, the crow bowed its head, flew off, and returned with a piece of pig’s lard which Cuthbert and his guests could use to shine their shoes. One particularly sweet legend asserts that sea otters would come sit upon Cuthbert’s feet, keeping the man of God warm in freezing weather.

Cuthbert not only received help from wildlife, but also offered protection to wildlife himself. He gathered a flock, not of sheep or of monks, but of eider ducks, giving them sanctuary on his little island and making him the first wildlife conservationist! It is a pleasant picture, to imagine Cuthbert surrounded by his animal friends during his prayers and praises to their Creator. Today the eider duck, with its yellow beak, black and white plumage, and expressive eyes is affectionately called “Cuddy’s duck” in recognition of its protector. (The population today is vast and far from the “endangered” spectrum!)

Cuthbert must have felt at home and at peace on his island, engaged in prayer and in stewardship of God’s creation. However, after a decade of this retirement, he was called upon to be the bishop of Lindisfarne. Cuthbert was reluctant but after much persuasion agreed – though it is said he made the agreement whilst shedding tears. As he had done all of his life, Cuthbert undertook the new calling with fervour, preaching and travelling extensively. Though he was a bishop, he continued to live as a monk in dress and diet. Like his elevation from monk to prior, his elevation to bishop did nothing to damage his humble heart. He gave food to the hungry and poor, and cared for those who were oppressed, always preaching repentance and forgiveness.

He remained bishop for only two years before being granted permission to return to his retirement, where he was likely the happiest he had ever been with nature and God. Sadly, within months of his return to Inner Farne, Cuthbert became ill and knew he was dying. A priest friend stayed with Cuthbert, and said he spent his last day “in the expectation of future happiness,” and later that evening went home to be with his Lord and Saviour.

Sainthood

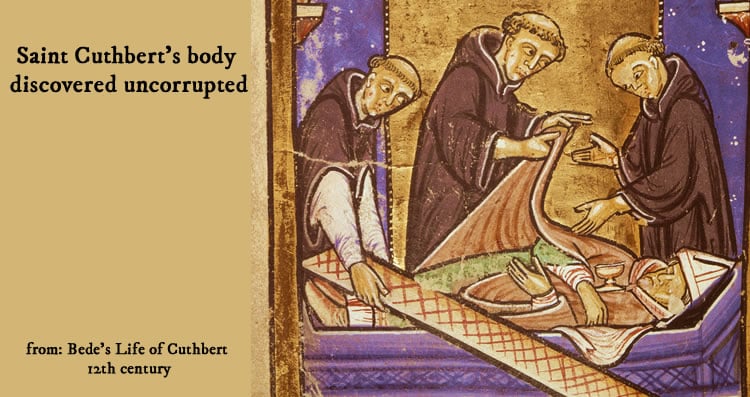

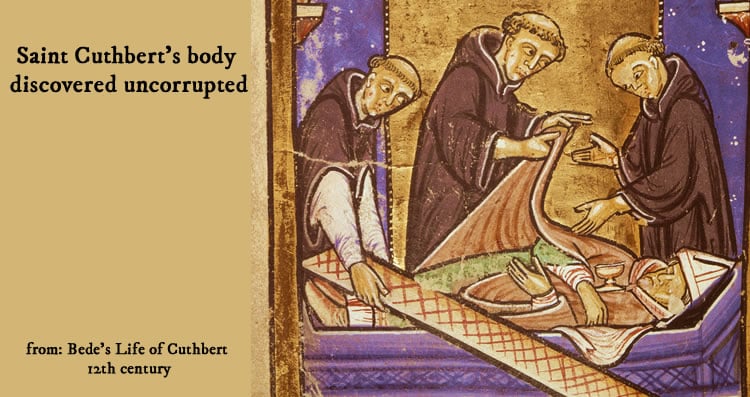

After his death on 20 March 687, Cuthbert was buried at Lindisfarne monastery. His monks, who had before been so problematic, were now overjoyed to have his bones there, for it comforted them to think that, in a way, Cuthbert was still with them. His legacy of piety and miracles lived on, and he was eventually venerated as a saint. Today he is often considered to be the favourite saint of England. Inspired by Cuthbert, the famous Lindisfarne Gospels were copied. They are beautifully and intricately illuminated copies of the Four Gospels made by the bishop of Lindisfarne “for God and St. Cuthbert.”

Cuthbert’s body, exhumed eleven years after his death, was discovered to be undecayed, encouraging many pilgrimages to be made to see the body, in the hope of receiving healing and forgiveness. During Viking raids, the body of Cuthbert was taken to Durham Cathedral for safekeeping, which is the place where his remains lie peacefully interred today, beneath a humble gravestone that would have been to Cuthbert’s liking. It reads only:

Cuthbertus.

Follow in Saint Cuthbert’s Footsteps

Today, you can still visit the Holy Island of Lindisfarne where Cuthbert lived.

Stay overnight on Holy Island to experience the solitude as felt by the monks on the Island, as the tide comes in and separates the island from the mainland. In low tide, take a walk to St Cuthbert’s Island, a small islet off Lindisfarne where Cuthbert spent many days as a hermit (ensure you only do this during the lowest time of the tide, as you may get stranded as the tide comes in). You can also take a day trip to Seahouses, from where you can join a boat trip to Inner Farm, to see Saint Cuthbert’s chapel on the island.

Much of what we know of St. Cuthbert of Lindisfarne appears to be legendary, but every legend must start with a grain of truth. If the stories are any indicator, he must have been a devout man who inspired those around him deeply, despite (and possibly also because) of his love of solitude.

Today, a modern statue of St. Cuthbert stands as a green-grey sentinel of the local priory ruins. His lips are pursed beneath his aquiline nose, his hands folded in contemplation, and his unseeing eyes watch over the Holy Island of Lindisfarne, which he once called home. It isn’t difficult to imagine why Cuthbert’s predecessors, Saint Aidan and his fellow monks, were apt to set up a monastery here. Beyond the practicalities of a fresh water source and green pasture, the isolation of the tides that make Lindisfarne an island twice a day and the sound of breaking waves, and spectacular sunsets all speak to the divinity of the Creator. And standing where Cuthbert stood, it isn’t so difficult to imagine him either – no longer just a figment of stone, but a living, breathing being separated from us only by time.

Much of what we know of St. Cuthbert of Lindisfarne appears to be legendary, but every legend must start with a grain of truth. If the stories are any indicator, he must have been a devout man who inspired those around him deeply, despite (and possibly also because) of his love of solitude.

Today, a modern statue of St. Cuthbert stands as a green-grey sentinel of the local priory ruins. His lips are pursed beneath his aquiline nose, his hands folded in contemplation, and his unseeing eyes watch over the Holy Island of Lindisfarne, which he once called home. It isn’t difficult to imagine why Cuthbert’s predecessors, Saint Aidan and his fellow monks, were apt to set up a monastery here. Beyond the practicalities of a fresh water source and green pasture, the isolation of the tides that make Lindisfarne an island twice a day and the sound of breaking waves, and spectacular sunsets all speak to the divinity of the Creator. And standing where Cuthbert stood, it isn’t so difficult to imagine him either – no longer just a figment of stone, but a living, breathing being separated from us only by time.